I don’t want to go all ‘pear of anguish’ here, and/or play into the lazy and tiresome stereotypes of medieval brutality, but … I did come across a tantalising little snippet on torture devices in a recent search of plea rolls, which I think is worth sharing with anyone who happens upon this.

It came up in an entry relating to an approver (approvers being those who ‘turned king’s evidence’ and accused their former associates, in the – usually forlorn – hope that they would escape punishment themselves).[i] There were relatively frequent assertions by these approvers that they had been coerced into taking on this very dicey role, confessing to their own guilt of a capital offence, probably having to take part in a judicial combat, and running the risk of immediate execution if they failed to make the accusation stick and their former associate was acquitted. Not a great option, in most cases, we might think (leaving aside the whole ‘confession is good for the soul’ thing). Such instances have been noted by others, including allegations of torture as a method of coercion, but I have not seen reference to the interesting and specific detail provided in one 14th C Yorkshire case.

In the King’s Bench plea roll for Michaelmas term 1343,[ii] we find a presentment by jurors of several wapentakes[iii] in Yorkshire regarding treatment of one William Cholle. William had, so they said, been in a prison (not specified where), and William de Rymyngton and John de Nessefeld, cleric,[iv] in whose custody he was, had taken him to the tower of York castle, and, once there, had drawn him on a rope and ‘on his fingers, put certain torments called pyrewynkes’ in order to force him to become an approver. He did not, however, become an approver. The jurors then went from specific to vague and general, stating that the accused had made many prisoners in their custody become approvers by the use of such tortures (though the jurors did not know the names of these unfortunates) and that William caused a number of men to be accused in sheriffs’ tourns, for profit (using false testimony and oaths, and then extorting money from them to have them let off).

I was expecting a quick ‘not guilty’, but no – the law caught up with William R, and he seems to have accepted his guilt (I trust, without the use of torture). He made fine with the king – the tariff was 20s. This, however, was offset by the expenses William declared for repairs to the doors and windows, and other repairs to the king’s hall of pleas at York castle. William was keen for this to be enrolled – presumably to protect him from any further action and/or attempts to recover the 20s fine.

So what?

Well, an interesting tale in relation to the two Williams. William C is, so far, a mystery: there may well be more to be found out, but it is at least interesting that somebody was known to have withstood torture. William R does not come out of it well, does he, but it is interesting that this was not treated as a massive abuse. What does that say about royal attitudes to the approver system? I think it supports the suggestions of earlier scholars that this was a fairly merciless thing, and also something seen as necessary for achieving an acceptable level of prosecution of offenders. If somebody like William R went a bit far, well, it wasn’t the end of the world.

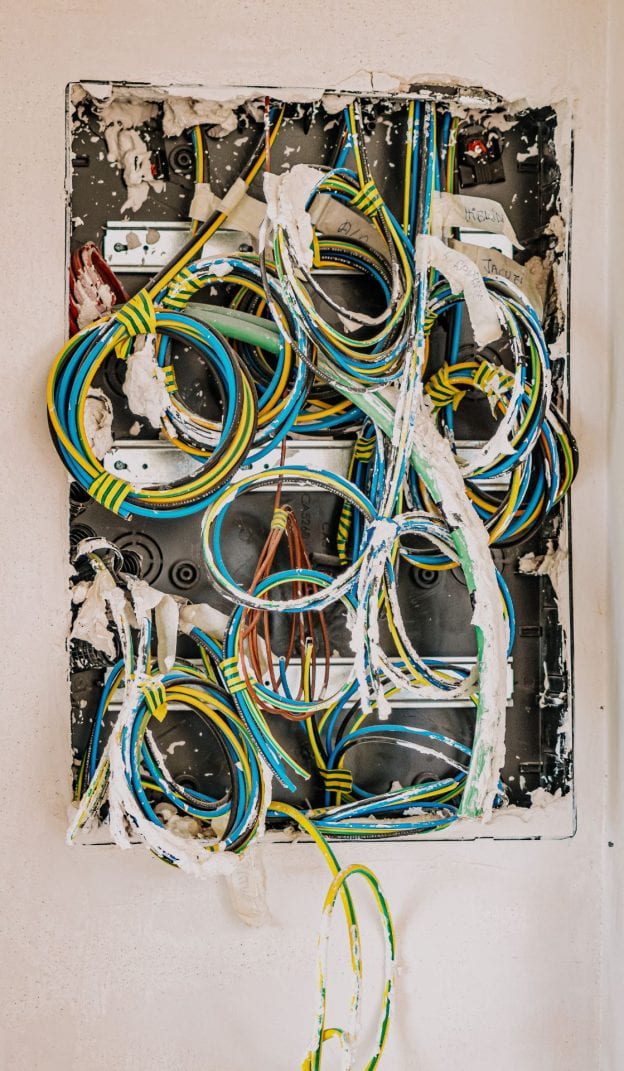

Finally, what about those ‘pyryewynkes’? Others may have come across this term in the past: I have not. They don’t seem to feature in the work of Musson, Hamil or Summerson. I can only speculate about their nature – they are plural: was there one for each finger? We will all be familiar with the thumbscrew – was this something like that, only multiple, and not just for thumbs? I assume that it was some sort of crushing or stretching device, but that may be a lack of imagination on my part. What is suggested by the name – it looks rather like ‘periwinkle’, so could it be a device which looked like small seashells? Or flowers? Or a word garbling Latin elements indicating tight binding? The flower seems more likely than the shell, given easily accessible definitions and etymologies.[v] Hard to imagine quite why the device was like a flower, if that is the idea. Probably a dead end, and perhaps more interesting anyway are two other things: first that it is named in English by the jurors, and, second, that it has a specific name at all. Both of these suggest, it seems to me, that this was something people in the wider community beyond the legal system knew about, talked about. So maybe, just maybe, it is a tiny signal that we medievalists should not take the defensive attitude towards ‘our patch’ too far, and be so quick to bat away all torture horror stories as ignorant modern nonsense, or shunt them forwards to the early modern period (that’s a favourite move with anything negative, isn’t it?). There may not ever have been a ‘pear of anguish’, other than in the minds of later fantasists, but a fair number of medieval people in York at least believed in the existence of ‘the fearsome pyrewynke’ …

GS

8/1/2024

Image – pretty, inoffensive, non-torturing, flower, vinca minor by Lydia Penrose, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

[i] See, in particular, A. Musson, “Turning King’s Evidence: The Prosecution of Crime in Late Medieval England.” Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 19 (1999), 467–79; F. C. Hamil, ‘The King’s Approvers’, 11 Speculum (1936), 238-58; H. R. T. Summerson, ‘The Criminal Underworld of Medieval England’ 17 Journal of Legal History (1996). 197-224; And I found this one useful on torture: L Tracy, ‘Wounded Bodies: Kingship, National Identity and Illegitimate Torture in the English Arthurian Tradition’, in D.E. Clark, L. Robeson, M. Nievergelt et al. (eds) Arthurian Literature XXXII (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer; 2015) 1-30. No doubt there is more I could read. My internet search engine did express concern, though …

[ii] KB 27/334 m. 17; AALT IMG 0320.

[iii] Wapentakes are jurisdictionally-relevant geographical subdivisions: this term is specific to the northern part of England.

[iv] He comes up now and again in official documents, e.g. here there’s a man of that name, county and time who has a job as keeper of the hospital of the Holy Innocents – and see the end of the next note.

[v] The trusty Middle English Compendium gives three meanings for ‘pervinkle’, including the shell. The flower seems to be the earlier ‘periwinkle’ though, and there is an intriguing association between the flower and execution, from Lydgate, in the MEC: pervink and pervinke – Middle English Compendium (umich.edu) ‘Thou hast … crowned oon with laureer hih on his hed upset, Other with peruynke maad for the gibet’- J. Lydgate, Fall of Princes (Bod. MS 264) vi. 126. I am not pretending I have read this – I haven’t – but intriguing nonetheless. And let me just go all-out conspiracist … there is an ecclesiastical document relating to a John de Nessefeld which is decorated with … flowers … Coincidence? I think not!

(And a quick ‘pear of anguish’ update … I am currently working through the complete ‘box set’ of detection drama, Bones (don’t judge: I find the puzzle solving very cathartic) and was intrigue/disappointed to see the POA featuring as a murder weapon in 4:15, with no correction about historical accuracy by Dr Brennan. It’s making me doubt the total authenticity of other aspects of the show …)